As a choice-based elementary educator, I believe that my students learn by making artistic decisions. I encourage them to explore the things and ideas that excite their curiosity, and I invite them to bring the objects of their interests—rocks, toys, stickers, anything—into our art studio. They are usually more than eager to do so. I also fill the studio with interesting materials and beloved collections of mine that the students can arrange and rearrange to make ephemeral works. Looking at collections with students, and making new collections together, opens unique avenues for enriching conversations about art. We closely examine the objects we collect, looking at them through the lenses of art-making and of being artists. Young kids are natural collectors, but they don’t always realize that, with clear intention, a collection can become a work of art. I talk about collections with my students because I want them to understand that artists can use a collection of objects as a way to make art, but artists can also create a collection of objects as a way to make art. Discussing contemporary artists who do both of these things can help to illustrate these ideas and start discussions about collections and art.

Allan McCollum at work. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 5 episode, “Systems.” © Art21, Inc. 2009.

When I share works by Lucy Sparrow and Allan McCollum with my students, they are always amazed by the sheer magnitude of the collections these artists are able to create. They respond with audible excitement to the artists’ work—to Allan’s collection of dinosaur-bone replicas and to Lucy’s entire convenience store filled with soft sculptures, made from the same felt that we have in our art studio. Small works can feel incomplete if seen on their own, but once a student considers making multiples, the project becomes more exciting, and the student develops a sense of direction and care for their work. When I encourage students to think of ways that they can create and/or use collections in the art studio, I refer to the work of McCollum or Sparrow.

Creating a collection takes time and persistence, but it also allows a young artist an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of a material or process. Kayla, a fourth-grade student, made one small plaster cast of her finger, but after she decided to make multiples, she ended up with fifteen little finger casts to work with. Eventually, a new idea began to emerge, leading to her Finger Necklace. Another student, Juan, created a few small origami pockets. Once he discovered that they fit neatly together, he decided to make a large collection that he used to create his paper sculpture, Time Portal.

“When students begin to collect, they also begin to curate.”

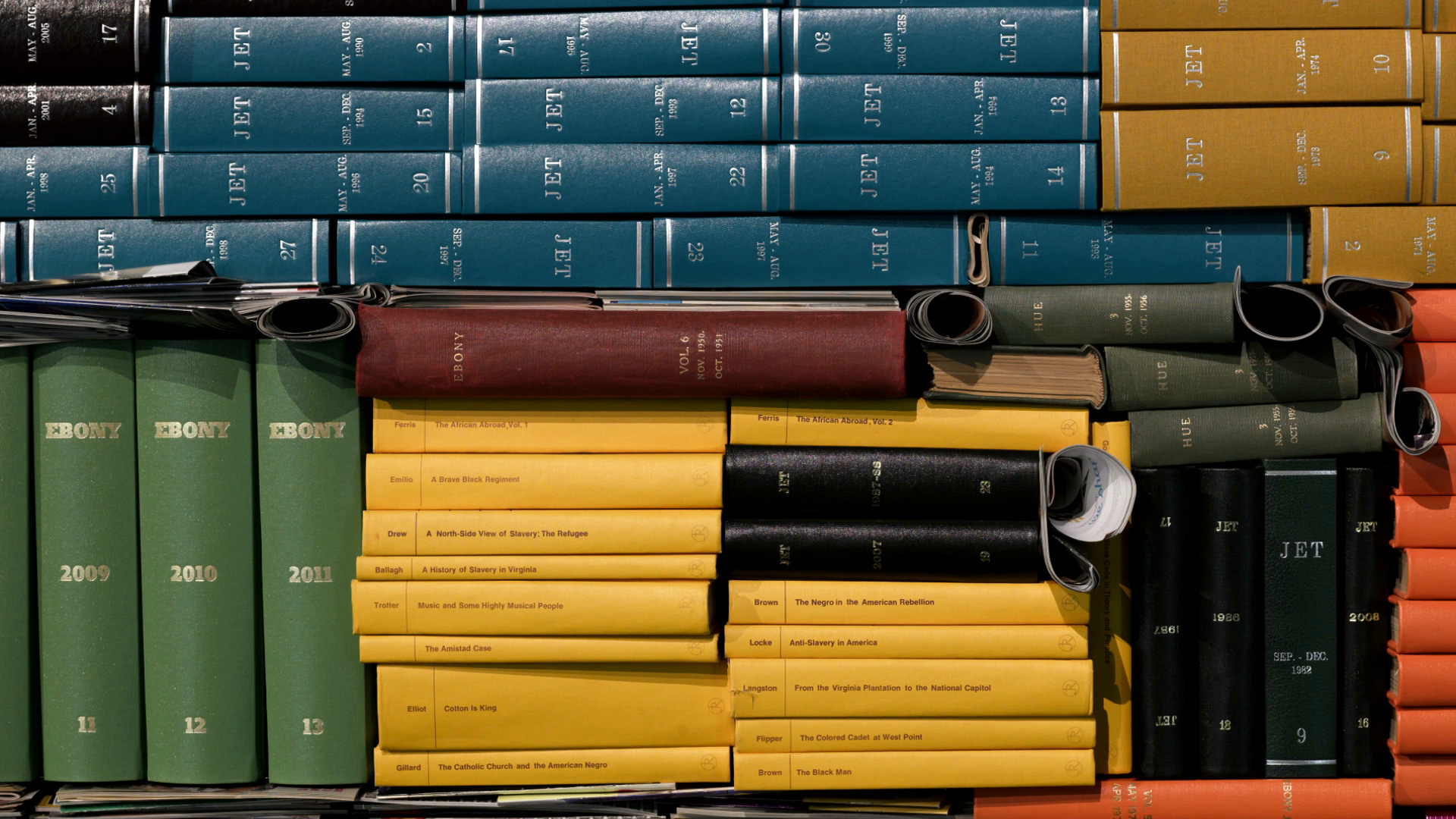

When discussing his work during the Art21 Extended Play segment, “Collecting,” Theaster Gates speaks about how collections are like “this little time capsule of things that were important to someone” and how he is “looking for the personality of people within their collections.” Even though the interests and aesthetics of my young students are often vastly different from my own, placing value on and honoring those interests are important ways to show respect to their developing creative personalities. When I share the work of contemporary artists with my students, I hope that they will be engaged and inspired and will recognize some of the artistic behaviors that we practice in our studio, all the while broadening their understanding of what art can be.

“Having collections activates the imaginations of young artists.”

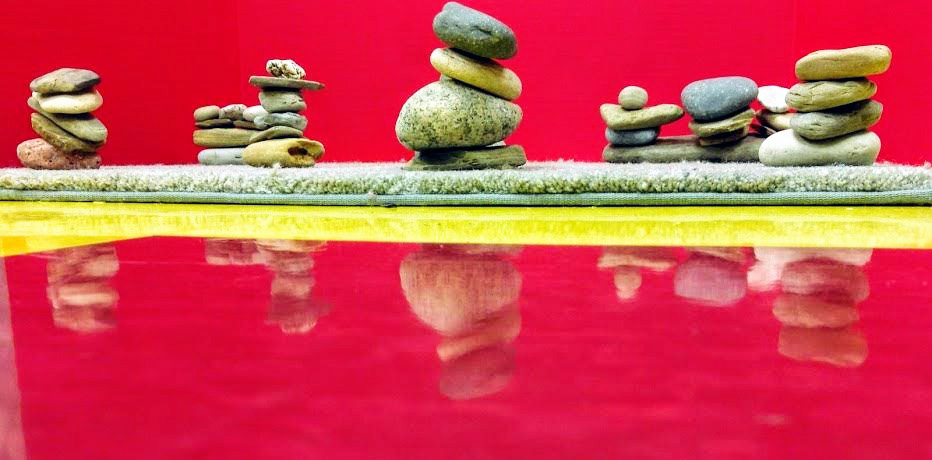

Some of the ordinary objects that Gates had collected and arranged—archiving the contents of a hardware store and binding issues of Jet and Essence magazines—took my students by surprise, which got us thinking: Why do people collect things? Do we have multiple objects in our studio that we can arrange in creative ways? What objects can we collect from home and bring into our studio? What makes some objects more interesting than others? When students begin to collect, they also begin to curate. We decided to create some studio collections; we began collecting things like plastic lids, buttons, sticks, rocks, and paint-chip samples from the hardware store. Having collections of small objects that are readily available for students to use in the art studio activates the imaginations of young artists. When students arrange these objects, they almost always have a detailed narrative that accompanies their work. They also learn the importance of documentation since the ephemeral sculptures must be photographed before the objects are returned to the collection bins at the end of class.

One afternoon, a few students excitedly called me into the hallway, saying, “Ms. Hergott! Ms. Hergott! Come out and LOOK AT OUR ART!” I walked out of the art studio to see that the students had carefully arranged a pile of freshly sharpened pencils into a visually pleasing row. It was a proud moment because they recognized not only their arranged pencils as art, but also themselves as artists. Incorporating the work of contemporary artists into my lessons and having conversations about that work has definitely broadened my students’ understanding of what art can be.

Powered by Börsen-Handelssysteme