Joe Fusaro. Suspension, 2016. Acrylic, graphite, gesso on wood; 12×12 inches. © Joe Fusaro. Courtesy of the artist.

Being an artist and an educator is easy, but making meaningful connections between the two vocations isn’t always simple. For many years, I separately practiced both: each day, when I arrived at school, I left my artist identity in the car and walked into class, determined to be a great art teacher but wary of the connections between being an artist and an educator.

One day, a colleague, Donna, asked me why I didn’t share my own drawings and paintings with the students. “I don’t want them to think that’s what I want to see,” I replied, reluctant to overly influence their techniques or styles. But Donna helped me to see that I could place my work alongside other art examples that I was sharing; I didn’t have to say it was my work.

“It gives street cred to the things we discuss and share in the classroom.”

I followed her suggestion. In doing so, I found that showing students that their teacher is an educator and a working artist had an unexpected outcome. While showing one’s art to students is a gamble and humbling experience, it gives street cred to the things we discuss and share in the classroom. For example, when students ask specific questions about technique and medium, I can offer first hand advice. When students inquire about exhibiting and working with galleries and institutions to show their work, I can share ideas about how to price work fairly. Sharing my experience helps students to overcome the fear of submitting work for the first time to a group of strangers. Over the years I have occasionally hosted studio visits for students, and I discuss the schedule I set for working on my art and strategies for juggling different projects and commitments. Sharing my creative practice and process may provide inspiration to students, in the same way that I’ve learned from the stories and strategies of artists like Laylah Ali, Mark Dion, and Kara Walker.

Laylah Ali, painting in her studio, 2005. Production still from the Art in the Twenty First Century Season 3 episode, “Power.” © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Laylah Ali joined our Art21 Educators Summer Institute in 2016 and shared with the cohort how she balanced teaching at Williams College in Massachusetts with her continued work as an internationally known practicing artist. Her recent project, John Brown Song!, brings together research and collaboration in a way that teaches through art.

Mark Dion inside his installation Neukom Vivarium (2006) at the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle, Washington. Production still from the Art in the Twenty First Century Season 4 episode, “Ecology.” © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Mark Dion, as a visual arts mentor at Columbia University School of the Arts, utilizes his work as a model for research and moving beyond the studio. For example, Dion’s Neukom Vivarium—which I have employed as part of my teaching in the classroom many times—serves as a reminder to all artists and educators that a primary goal of teachers is to provoke dialogue and discourse.

Kara Walker, standing at Algiers Point, New Orleans, in front of her piece Katastwóf Karavan (2018) in Prospect.4. Production still from the Extended Play episode, “Sending out a Signal.” © Art21, Inc. 2019.

In an Art21 Extended Play segment, Kara Walker discusses her ambivalence about being a young educator and having the responsibility to tell students how to be a successful artist. But she eventually admits to herself that she, like many artist-educators, must have something of value to offer young students interested in becoming artists. Walker reminds us that “there is no diploma that declares someone an artist” but rather a process of becoming an artist, after making the decision to be one.

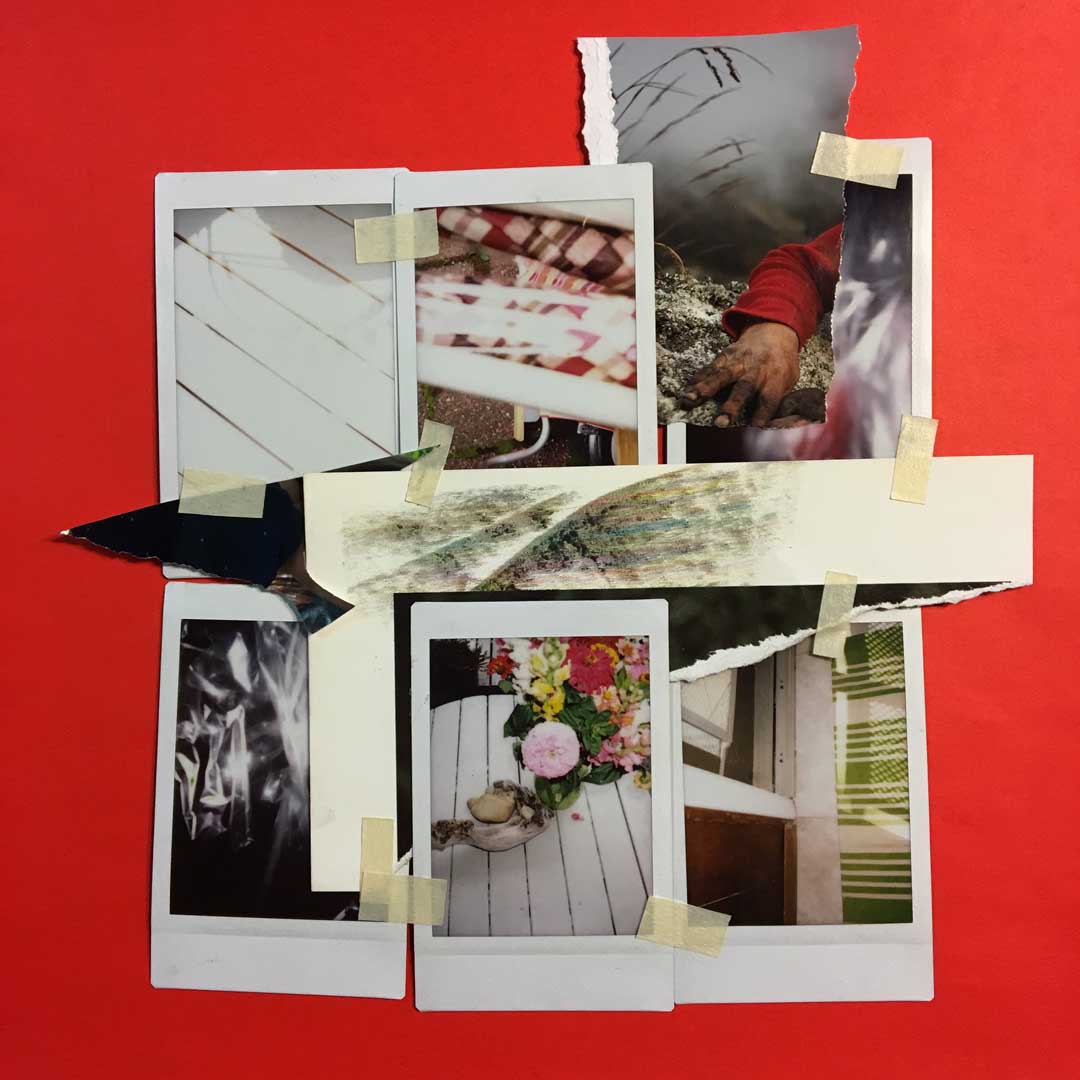

Joe Fusaro. Prayer Book, 2013. Mixed-media on paper; 20×15 inches. © Joe Fusaro. Courtesy of the artist.

My artwork is often fueled by what goes on in the art classroom. Scrap paper from a printmaking unit, sandpaper from the floor of the ceramics studio, and even discarded photo experiments have served as launch pads for entire works, such as Prayer Book. Because these scraps are the products of labor and process, they inspire connections for me outside the classroom. Conversations with colleagues and even sudden movements or gestures of someone I’m working with sometimes are recalled later in the evening, at the studio.

While I work on my art, I often have my students in mind. Many pages of my sketchbooks include lists of artists, media, and other things I want to share with the people I teach. Like all teachers, I know that my students follow me around, even into my studio.

Bite Your Tongue: Works by Joe Fusaro is currently on view at the Cotuit Center for the Arts, Falmouth, MA through June 9, 2019.

Powered by Versicherungsvergleich