Kevin Beasley in his studio.Production still from the New York Close Up film, Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials, 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019.

Editor’s Note: “Sound has always been important to me, and it has increasingly become a way for me to process the world,” reflected Kevin Beasley in a recent Art21 New York Close Up film, which offered a look behind the scenes as the artist prepared for his Whitney Museum exhibition, A view of a landscape. Mark Bradford, also celebrated for his material-oriented practice, is known for creating large wall-sized collages and installations from found materials that respond to social structures of American cities.

Featured below is a dialogue between Beasley and Mark Bradford, who met at Yale University, where Beasley was an MFA student and Bradford was a visiting artist. Here, the two share their experiences, from navigating the world as Black men to their approaches to materials and creative practices. The dialogue—originally published in the book Kevin Beasley, in tandem with Beasley’s first major museum exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, curated by Ruth Erickson, the ICA’s Mannion Family Curator—provides insight into two great creative minds at different stages of their careers.

Kevin Beasley: We first met in the spring of 2012 when I was doing my MFA at Yale, and you were a visiting artist there. It was so generative, and there was an immediate connection, so as a starting point for our conversation I wanted to return to some of the concerns you raised, and the subject of the studio. When you came into my studio, I remember that I almost immediately started getting into the social and political content of my work, and you interjected by recognizing my investment in these relationships but insisted that I look at an even broader picture within my practice, and more specifically, to not box the work in. I’m paraphrasing here but you said that people always try to categorize you and see you in a way they want to, particularly as a black artist, so it’s important to allow the aspects of your interests that are outside of stereotypes of the black identity to surface—that which is unexpected. A lot has occurred since 2012, so as an attempt to check in on these ideas, I’m curious about how this continues to factor into your decisions in the studio, if at all? ¹

Mark Bradford: Did I, at Yale? Well good. What struck me when I first entered your studio was your thought process, and your investigation of materials. Yes, black artists really have to “claim” that space of fluidity as we work through our ideas and investigate, to be able to say: “I’m figuring my shit out.” I would look at the sculptures and your fascination with music as a jumping off point for a kind of meditation. And I remember you being very clear about what your interests were and I think since then you have stood firm. That’s why your work rings true. Oftentimes what we learn in grad school is a theoretical European gaze, as if nothing or anything else would or should be the impetus for the work. But I believe that being black demands a kind of double speak/double consciousness à la [W. E. B.] Du Bois. The black male body is one of the most politicized bodies in the USA. How can we turn fully away from the political, social, and national debates?

Mark Bradford in his studio, Los Angeles, CA, 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

“An audio recording of a riot has a particular rhythm and timbre.”

—Kevin Beasley

KB: I would even suggest that the attempt to turn away, if that was an interest, would have to recognize the social and political debates in order to know from what one is turning. It’s just not a useful exercise to turn one’s back on these issues without a sense of its trajectory. This is one reason why your video work in the American Pavilion² was so resonant, because it embedded this double consciousness—within the work there is a walking away from the gaze and yet towards something beyond our sight and vision—the man’s gait actually suggested a sense of resolve; something more generative and internally resolute. It’s a very nuanced and multilayered work in that context because it produced an image of representation that laid claim to this fluidity. You made visible the act of walking away from the gaze. I saw its function parallel to the treatment of the building itself, within which abstracted gestures could take on multiple reads with a kind of sociopolitical awareness. For example, can one see within the work a level of awareness to these concerns within abstract gestures and forms without prior knowledge of that interest/relationship? What is being abstracted? And how does that action continue to carry the cultural weight of those materials? I think this is why I have an interest in this kind of abstraction, the kind that utilizes these cultural materials as a mode of exploration. I ask these questions when working with music and sound clips—does the audio from a significant/tragic political event still carry its importance when it is recontextualized? How much abstraction can this go through before it loses its immediacy? Or even urgency? Because I really think that an audio recording of a riot has a particular rhythm and timbre.

Kevin Beasley in his studio.Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019.

MB: Can you talk a little more about your use of materials? It seems that you have such a rich array, a mature gaze. How did that develop?

KB: Materials are always an expanding aspect of my practice because as much as I enjoy the technical understanding of how these things come together, I am constantly questioning what can be a viable material to use, to explore the ideas I am engaging with. Materials sometimes drive an artwork and at other times they are the byproduct of an experience I’ve had that either left me vulnerable, or left me unable to express something about that experience with words. For example, seeing a cotton field for the very first time in my life left me speechless, not just because of slavery and the American cotton field, but also because of its materiality—its transformation, yet its essential quality. A cotton blanket isn’t that far removed from a raw cotton boll—there is actually very little noticeable processing. That direct transformation is very important because at its core, it is unlike anything else.

Kevin Beasley in his studio.Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019.

There are no substitutes when you consider the entire life of the material. So I am constantly thinking about how I get to an understanding of my surroundings (people, places, and such) in all of their nuances. It is how I end up using housedresses and kaftans in some work and then a crushed Cadillac Escalade in another—they are both connected to my navigation of the world because I’ve had compelling questions about those objects, people who have had an impact in my life, and the effects of society on the way I am perceived/perceive myself. It’s myriad; I become overwhelmed by the varying levels of emphasis placed on subjects, context, and how much that can fluctuate in the process, but I’m constantly trying to develop and refine my approach. Something that worked for me in the studio a year or two ago just may not now because my thinking and knowledge on what certain materials evolves.

MB: Your projects generally have such a strong materiality; how do you connect these with your work with sound, music, with vinyl? Are these an expansion of your practice, or did this work develop simultaneously?

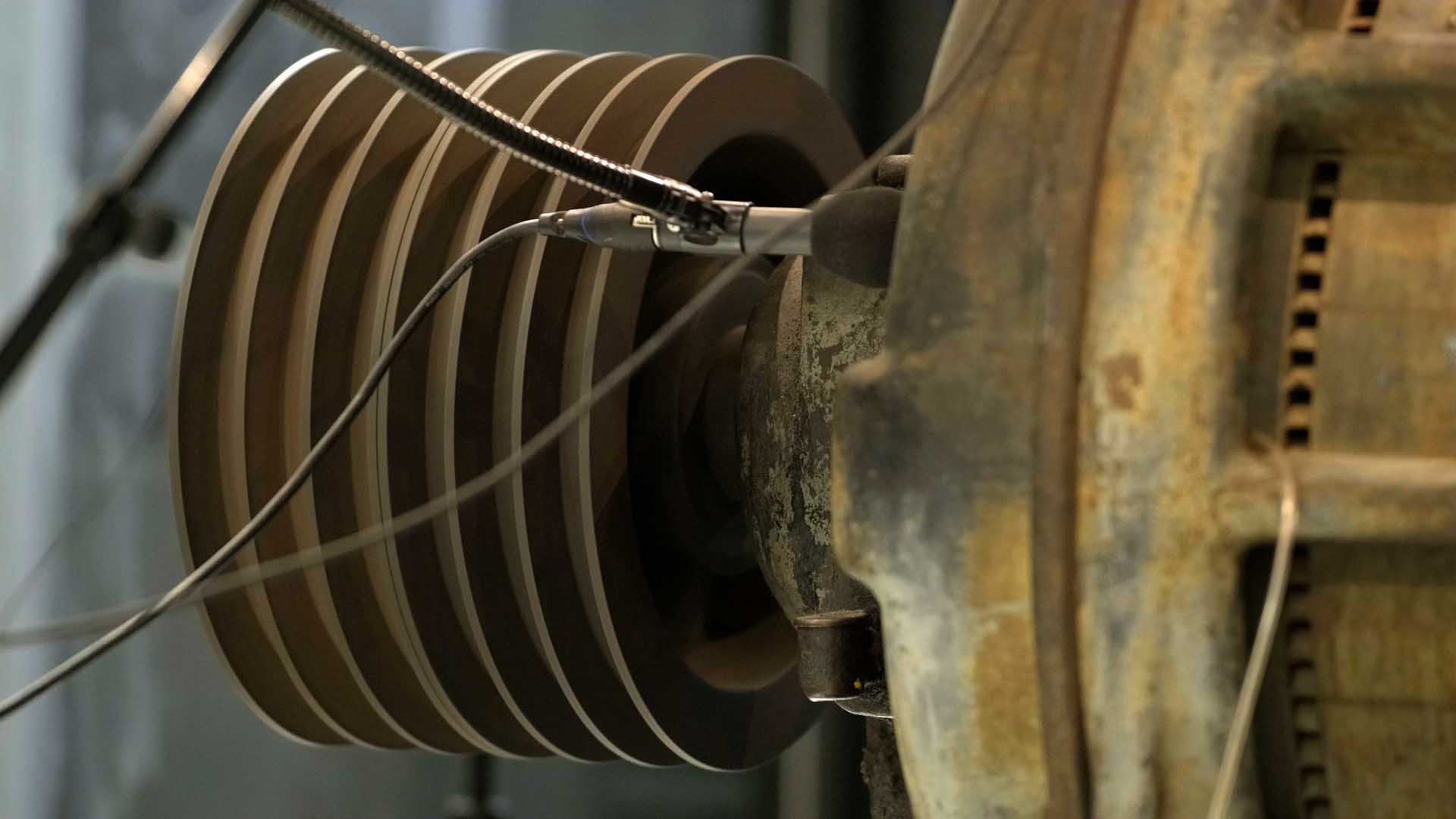

(Top) Kevin Beasley inside the vitrine with the Cotton Gin Motor. (Bottom) Detail of the cotton gin motor. Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019.

KB: I’ve played drums since I was thirteen, and I have some basic sheet music reading ability, but for the longest time, I’d always kept my music separate from art. The lines began to blur while I was in graduate school, specifically because of my increasing interest in vinyl and mixing. Mixing was really the “aha” moment because I’d never thought about how tactile, how physical, and how transformable sound and music could be through vinyl. Once I’d invested a bit of my student loan money into some DJ equipment, it all became another set of sculptural tools. I saw them in the same way I viewed any of my other tools and materials, except instead of plaster, resin, or clothing, it was recordings and the sound waves of various frequencies. What I had worked so hard to keep separate for the sake of some kind of purity became the very thing I needed to break down and mix up. So in one way, my practice is invested in the discovery of these connective aspects of materiality.

“If there was more of an emphasis focused listening, I think we could begin to understand more nuance in our daily encounters.”

—Kevin Beasley

I’ve become especially interested in recorded sound because it provides us with a mark of time, like an etching in a wall or an ancient relief. It becomes materially significant because it describes the condition of a space through other means than our sense of seeing, which we rely on so heavily to navigate the world. I just can’t continue to move through society without asking questions about what I’m hearing, what is being said, the noise of the world. I could go on forever about it, but I will say this: the immediate urgency I find in sound—even more so when it comes from a physical object such as vinyl—is the necessity to listen and give it time and space. It’s so much about observation and actually submitting to what is being projected and that is a very vulnerable and revealing space to commit to, because you open yourself up to hearing something you may not understand, like, or agree with. If there was more of an emphasis focused listening, I think we could begin to understand more nuance in our daily encounters, effectively refining our relationships with one another and the world we inhabit.

MB: So with mixing and vinyl becoming sculptural tools, how did you begin to craft a language around them? I mean, there ain’t a lot of people using this particular toolbox. I remember DJ Spooky [Paul Miller] years ago—nothing like what you do, but his name comes to mind. There is always a sense of purity, isn’t there? Blur, remix, and acceleration always come to my mind when I’m looking at your work. I remember the earlier sculptures, and then the shift to mixing and I noticed there was a lot of buzz and I thought: I hope he keeps going. I love that you did and that you keep pushing.

Kevin Beasley in the studio. Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kevin Beasley’s Raw Materials,” 2019 © Art21, Inc. 2019.

“Language is always a bit late to the party isn’t?”

—Mark Bradford

KB: Language can be tough for me because I always feel like what I’m describing is still not what is happening, or that the words I am finding are foundational to something else that is more interesting and/or relevant. Working with vinyl, I was literally looking for words to describe the techniques—kind of a pun right there, since the Technics SL1200 is the industry standard turntable for DJs—for mixing and so much of DJing and mixing language relates to art making. Scratching has two important meanings to me in both music and in making sculptures, not to mention the word “mixing.” I do think a practice of questioning is essential, and a lot of questions were produced, but I want some answers along the way too. I think the words I cling to describe some of the answers I’ve found within a much bigger trajectory. I’ve also wanted to ask you about this because you find language so naturally—it’s really sharp, funny, but also really relatable—even when speaking about adversity your approach is very uplifting. How do you think about language in relationship to your artworks and your practice?

MB: I agree—language is always a bit late to the party isn’t? I think you do a good job of leaving room for a certain fluidity, much like your mixing. What is always the challenge is to maintain that sense of fluidity as you change and grow. Language is not and will not ever be perfect. It’s like that childhood friend you should have dropped long ago but you still cling to the childhood memories although you’ve been let down a million times. That’s language for me: flawed. But I often use humor to skate along the edge of an idea, to maybe push it into a space that is a little more uncomfortable under the guise of “ha ha ha.” Really, you find out what fits after you kill the theoretical “daddy” that sits on all of our shoulders post-grad school. I’m curious to know where you are now. You’ve been out of school for a few years now and are critically questioning things. Does it effect how you think about how to use language, or what has recently changed?

Mark Bradford in his studio, Los Angeles, CA, 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

KB: I definitely feel the weight of the theory daddy, even though I never read much theory—I’m not good at recalling references and names, and it is taking me time to let my emotions and senses take over rather than my mind and analysis. It’s an ongoing battle and shows up in the way I try to speak about it. But I do feel a change, and in fact, while I was in grad school I had these heavy emotional experiences. It made me think, okay—this is the potent stuff that I can’t rationalize nor can I ignore it, and most importantly, I really didn’t understand it. In the years since grad school, it has been so much about how to be someone who is critically questioning things via these emotions and feelings. And really, I would say that the critical questioning I’m engaged in is a severe case of skepticism about where I am in society. There is true value in those feelings, especially if you’re an affectionate and passionate person, which I consider myself to be. I just hope to develop a collection of words and experiences that can be read by others who can relate and connect with them; and maybe that can breed a generative society.

[1] This conversation was conducted over e-mail from September 1–October 25, 2017.

[2] Mark Bradford represented the United States in the 57th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale with the exhibition Tomorrow is Another Day (May 13–November 26, 2017).

Powered by Vergleichsportal