Writer, artist and activist Avram Finkelstein reflects on the Science=Death movement, image commons, and the strength of the collective voice.

The post The Intrinsic Openness of the Hive Mind first appeared on Art21 Magazine.

The Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death, 1987. Poster, offset lithography; 33 1/2 × 22 inches. Courtesy of Avram Finkelstein

We’re so inundated by images that we think we know everything about them. We give images tremendous weight, even though they’re really just the set decoration of our social landscape—the sky, rocks, and trees—and we barely think twice about how they came to be or appear in front of us; they are like the background in a cartoon. Images help us define how we think about ourselves, collectively, but most of us never consider them critically, even images that resonate with us, like “Silence=Death.”

For many who responded to its call, “Silence=Death” has come to represent a turning point in the struggle for queer self-determination, and so, as images go, it casts a mighty shadow. Still, if one shifts one’s focus away from the center of what we believe this image represents and toward its lengthening late-twentieth-century penumbra, the institutional uses for an image like “Silence=Death” have less to do with political agency and more to do with its gradual repositioning within our image commons—the storytelling landscape created to reify late-stage capitalism—alongside brands like Apple and Doritos, and the recent commercial viability of Stonewall riot celebrations.

“’Silence=Death’” didn’t create the need for political agency; it just named it.”

It’s irrefutable that AIDS activism was a pressure cooker that expedited AIDS-drug development, but deregulation of the drug-approval process was a request that federal agencies were happy to oblige. And so, continued institutional deployment of images like “Silence=Death” actually serves to privilege dissent that is presumed useful—dissent that perpetuates capitalism directly or creates cultural byproducts, like the “Silence=Death” image—over resistance strategies that are considered destructive, like interventions that threaten structural ownership or property. The institutional use of “Silence=Death” also situates branding as life-saving, if one is willing to put aside the presumptive neutrality of access to treatments and pharmaceutical intellectual-property rights. Moreover, viewing the efficacy of “Silence=Death” as a representation of activist branding savvy ignores the six years of torment leading up to the birth of the image, and leapfrogs to the marketplace that AIDS eventually became, in much the same way that corporate sponsors imagine their subsidy of the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall as an investment in a new generation of legacy consumers, rather than a hat tip to rioting.

Likewise, it’s a misunderstanding of the nature of political agency to refer to cultural production like “Silence=Death” as having pushed AIDS activism into being, when the reverse is much closer to the truth. “Silence=Death” didn’t create the need for political agency; it just named it. The movement was the inevitable response to a slow-motion train wreck of suffering and despair, once it became clear we were experiencing it collectively. The Silence=Death Project just happened to poster the streets of Manhattan at the same moment that hundreds of people assembled at the New York LGBT Community Center in an effort to act on their desperation. If individuals hadn’t organized themselves during the coincidental saturation of “Silence=Death” posters in the streets of Manhattan, the poster could have simply come and gone, like millions of others in New York.

The Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death, in situ, 1987. Poster, offset lithography; 33 1/2 × 22 inches. Courtesy of Avram Finkelstein.

It’s reassuring to imagine that movements reflect a collective decision to act; they do, but a movement happens one person at a time and evolves before taking its collective shape. Once a movement takes form, it continues to morph, and the tremendous power of collective political action eventually eclipses the stages of its development, making it easy to overlook the power of the individual voice. Individuals make movements, in much the same way they make marketplaces: incrementally, cumulatively, as responses to the commonalities of human experience or of messaging that represents it, as extensions of consensus (however frail or evanescent they might be), and as articulations of a desire to be considered or seen.

“There is no idea that can’t be improved by multiple minds.”

One of the harsher awakenings within Trump’s America is how wild the drive to express individual agency can become and, within the isolated cloisters of social media, how frequently rageful it is. Online performances of the primal urge to be heard exist on both sides of the political commons. Luckily, the desire for collectivity does as well: to belong, to act with others, and to be situated in a landscape of shared social contract. Collectivity is as primordial as rage, and it can be as easily fostered, guided, and nurtured.

Avram Finkelstein/Queer Crisis Flash Collective, Queer Crisis, 2014. From a workshop co-organized with Dan Fishback, sponsored by the Helix Queer Performance Network and the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, New York. Crack-and-peel stickers; 4 x 4 inches. Courtesy of Avram Finkelstein.

Based on dozens of workshops on collective practice that I’ve conducted, during which I assemble a group of strangers to create a political intervention in a public space, I have observed the presence of several noteworthy traits. The first is that inventiveness, originality, incisiveness, and analysis exist in every roomful of strangers. The second is a surprising willingness to trust in collectivity, however momentary. The third is an urgency to participate, to go “on the record,” and, when people feel they are not alone, to do it publicly. The fourth is the intrinsic openness of the hive mind, which we generally witness as closed (to the point of unkindness) in the social spaces of the Internet, spaces we unfortunately misunderstand as communal spaces for dialogue. As a practiced propagandist, I can assure you that they are not. The Internet is a space for message delivery, not for listening, and dialogue depends on listening.

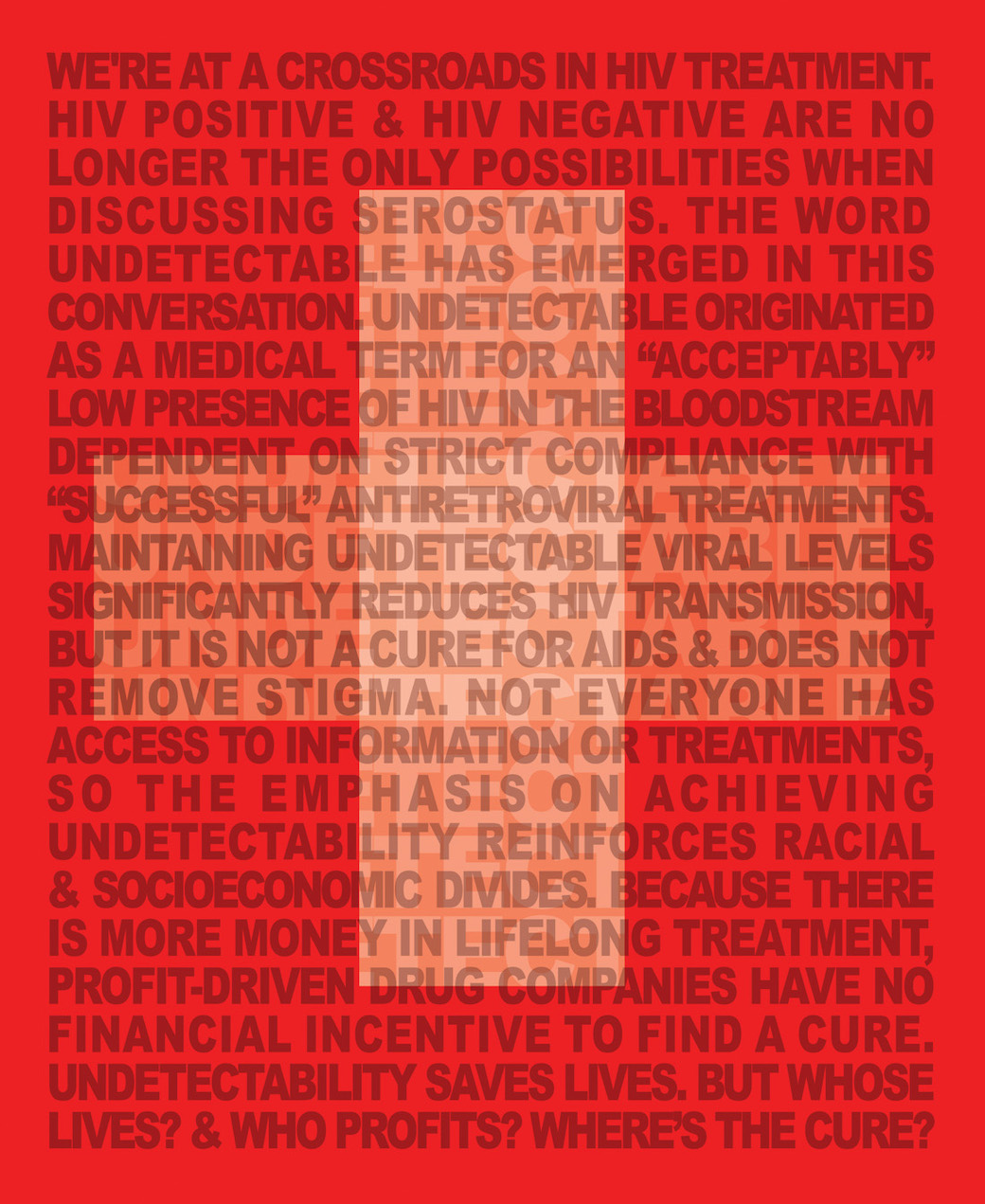

Avram Finkelstein/What Is Undetectable Flash Collective, What Is Undetectable?, 2014. From a workshop co-organized with Jason Baumann and Visual AIDS, sponsored by the New York Public Library. Lenticular postcards and lightboxes, 6 x 6 inches and 36 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the Avram Finkelstein.

“When asked, most people are hungry to articulate their view of the world”

I have been endlessly surprised by the startling intelligence of collective endeavor. There is no idea that can’t be improved by multiple minds. Every exercise of collective action I’ve conducted produces not one but several powerful statements of social concern. I’m convinced that if we could sequester a subway car full of strangers at the Jamaica-179th Street stop of the F line in Manhattan, with them we could devise multiple works of public art by the time we got to the Coney Island–Stillwell Avenue stop.

The inherent brilliance and innate aptitude of the collective mind is a well-kept social secret, one that institutional power structures hide from us, for obvious reasons: they are very afraid of it. As well they should be. When asked, most people are hungry to articulate their view of the world, and they pay much closer attention to it than we are led to believe.

The post The Intrinsic Openness of the Hive Mind first appeared on Art21 Magazine.