For an art form so daring, defiant, and overwhelmingly public as graffiti, it is too often dismissed, ignored, and (in some cases) made invisible, disappearing into the barrage of visual information around it. Encompassing everything from large-than-life paintings to train tags or the scratching of one’s moniker into an air-conditioner grill, graffiti both animates and disrupts our landscape. This way of working was at the heart of Margaret Kilgallen’s practice.

The post Slaughter first appeared on Art21 Magazine.

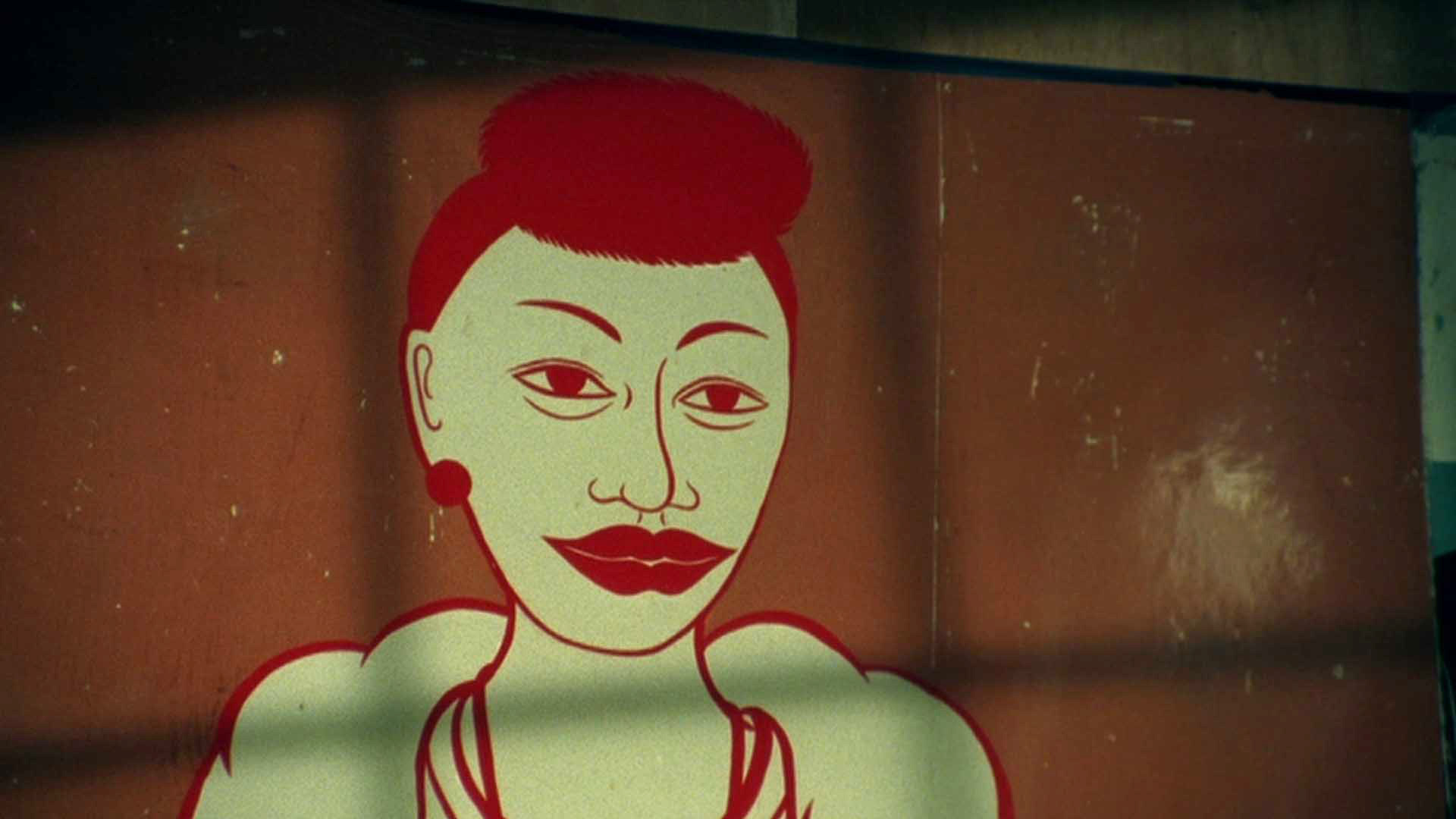

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2019.

For an art form so daring, defiant, and overwhelmingly public as graffiti, it is too often dismissed, ignored, and (in some cases) made invisible, disappearing into the barrage of visual information around it. Encompassing everything from larger-than-life paintings to train tags or the scratching of one’s moniker into an air-conditioner grill, graffiti both animates and disrupts our landscape. It finds a home on the sides of buildings, buses, and train cars, carving out a place on benches and signposts while it hides in plain sight among billboards and posters. Yet what separates graffiti, no matter the placement or scale of the gesture, from other images permeating and circulating through public spaces is its wholehearted embrace of the human hand: through graffiti, one makes one’s mark directly onto and into the world.

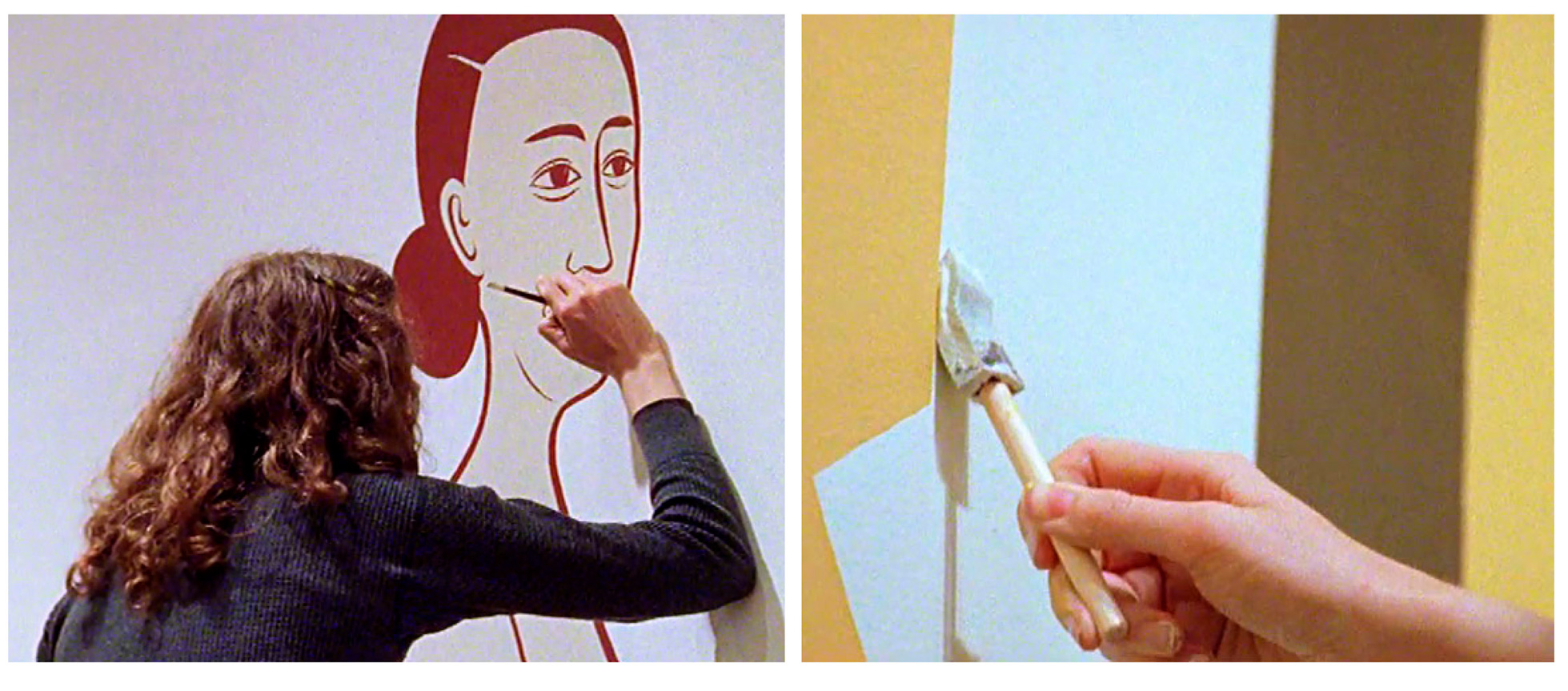

Production stills from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2019.

For Kilgallen, graffiti was about people reclaiming space by putting forth images, words, and narratives rather than accepting those chosen for them.

This way of working was at the heart of Margaret Kilgallen’s practice. Eschewing the use of a computer, she believed in the power of the human hand, celebrating the beauty that comes from working toward perfection: trying to draw a straight line, only to see how it would inevitably waver. For Kilgallen (1967–2001), the beauty was in the gesture of using one’s hand to craft something for the world at large. She believed in making open, accessible work that people could gather around, in a communal visual experience, and she worked extensively in public spaces, chalking up trains and painting murals and signs. She found it unsettling that people dismissed graffiti as vulgar and ugly without pausing to consider the visual onslaught of advertisements plastered throughout the city. For her, graffiti was about people reclaiming space by putting forth their images, words, and narratives rather than accepting those chosen for them.

Production still sequence from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2019.

Living and working in the Mission, in San Francisco, from 1989 to 2001, Kilgallen was heavily influenced by the city, in particular the breadth of public art and creative expression in that neighborhood. She was especially inspired by the Mujeres Muralistas, a group of Chicana/Latina artists who painted large outdoor murals. Beginning in the early seventies, this all-female collective painted images of influential Latin American women alongside portraits from their community: mothers, daughters, and workers engaging in everyday activities. Countering both the lack of support for women artists and the lack of images of women within the Chicano mural movement, the Mujeres Muralistas wanted to illustrate that women’s voices not only matter but also deserve to be shared. This resonated deeply with Kilgallen, who firmly believed in changing “the emphasis on what’s important when looking at a woman.”¹ Like the Mujeres Muralistas, Kilgallen believed that there should be more space for women, not just in the visual arts but also in a holistic sense, in the world at large.

Left to right: Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Mendez, Patricia Rodriguez, and Irene Perez. Photographer unknown, courtesy of El Tecolote archives and Foundsf.org

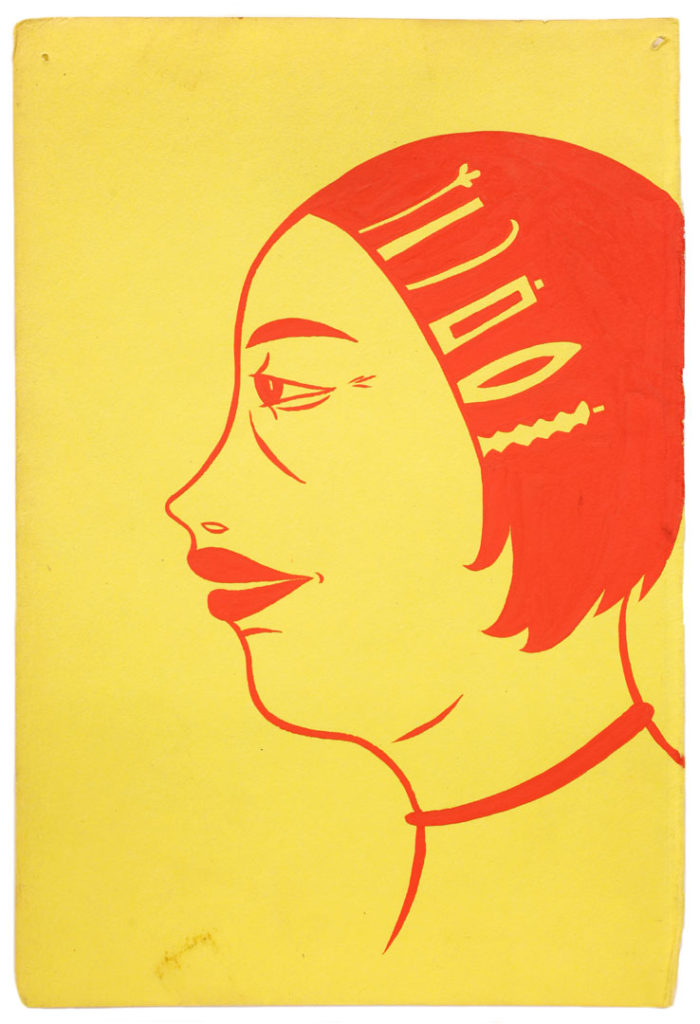

Margaret Kilgallen, “Untitled” (2000), Acrylic on paper, 8 1/4 x 5 1/2 inches, Courtesy of Ratio 3, San Francisco

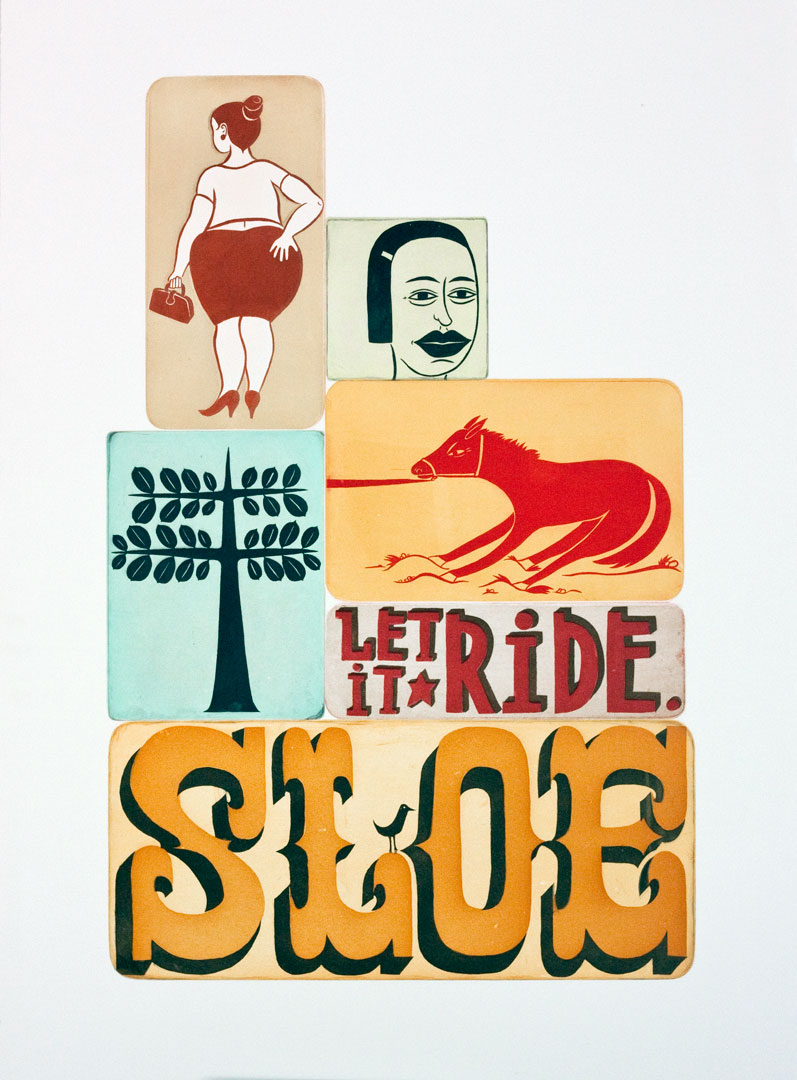

In Kilgallen’s work, women are front and center. Rendered in sharp, bold lines, they smoke, drink, fight, ride bicycles, and surf, sharing space with words that activate and emphasize their presence. “STEADY,” “PRIDE,” and “SLAUGHTER” are just a few of the words that appear. Mining the histories of printmaking, folk art, and folklore, Kilgallen borrowed and collected phrases, names, and terms, interweaving them to create her visual language. She was particularly enamored with colloquial and vernacular speech, reclaiming language that had fallen out of fashion or favor. In her world, we oscillate between time and place: walking the main drag, drinking sloe gin, perfecting our drop-knee technique.

Her use of the word slaughter is particularly poignant, as it refers to an actual person—the old-time musician, Matokie Slaughter (1935–99), a creative influence on Kilgallen—while it can be read also as another word for kill, massacre, or slay. Kilgallen adopted Slaughter’s moniker and wrote variations of it (“Matokie,” “M.S.,” “Slaughter,” and “META”) everywhere she went, in large murals on bridges, train cars, and water towers, and subtly, on the parking meters in the Mission. Her claiming of Slaughter’s name was an act of celebration and protest, a means to reclaim space for a woman whose talent and work had been rendered invisible by and for many others. Kilgallen, by writing Slaughter’s name into the world around her, eloquently reminds us that our world is made up of so many people who have been rendered invisible, ignored, and forgotten.

Margaret Kilgallen, “Sloe”, 1998. Color aquatint etching with chine collé on somerset soft white paper, Image: 27 3/8 x 17 1/2 inches; Paper: 36 x 24 1/2 inches, Edition of 30, Courtesy of Paulson Bott Press, Berkeley

Kilgallen’s work speaks to the ongoing legacy of material culture in the expression of the human condition. Image and language are the means by which we share our experiences with one another, in the hopes that we might see our world and ourselves in new ways. When a mark is made on a surface in a public space, part of that gesture and action is a declaration—I am here, I exist, I matter—a form of communication and sharing with one another. Kilgallen both recognized and celebrated these marks as she encountered them, from the work of the thriving community of artists working alongside her to the unknown writers and taggers making their marks all over the city.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2019.

A place is made by those who inhabit it. In some cases, it is built from the ground up; in others, it is reclaimed by those who are not reflected in the dominant narratives and images. Graffiti, as an art form, is temporal and ephemeral in nature, alluding to that of a body in space. Like us, it must contend with the weather and the effects of others, endlessly at the mercy of construction and change. And yet while it might fade, be painted over, or even be destroyed, it affects the places where it lives, seeping into the memory of those who encounter it. It is fitting that graffiti artists are called writers, as their mark making is akin to storytelling, embedding an ever-expanding set of characters and narratives into the public sphere. The same can be said of Kilgallen, whose art and life were inexplicably connected but whose hand can be felt—and still seen, if one knows where to look—all over the city of San Francisco.

¹Susan Sollins, “Excerpts from an Interview with Margaret Kilgallen for Art21,” Margaret Kilgallen: In the Sweet Bye & Bye (Los Angeles: Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater, California Institute of Arts, 2005), 126.

The post Slaughter first appeared on Art21 Magazine.